Applications & Considerations for 10 Gigabit Ethernet & Beyond

It is critical for networking professionals to have and understanding of these new Ethernet standards and the diverse range of interconnect hardware that make these technologies possible.

Download the Full Whitepaper (PDF)Executive Summary

Ethernet is a group of networking technologies that are designed to facilitate the communication of various devices over a local area network (LAN). Ethernet operates on the Data Link Layer of the open system interconnection (OSI) model, which is the conceptual model used to standardize data packet framing and enabling error-free communication. Ethernet is a group of networking technologies that are designed to facilitate the communication of various devices over a local area network (LAN). Ethernet operates on the Data Link Layer of the open system interconnection (OSI) model, which is the conceptual model used to standardize data packet framing and enabling error-free communication. Ethernet is a group of networking technologies that are designed to facilitate the communication of various devices over a local area network (LAN). Ethernet operates on the Data Link Layer of the open system interconnection (OSI) model, which is the conceptual model used to standardize data packet framing and enabling error-free communication.

Key Takeaways:

- 10 Gigabit Ethernet (10 GbE) is increasingly essential for modern networks, supporting the convergence of data, voice and video traffic, especially in datacenters and high-performance environments.

- Migration from Gigabit Ethernet to 10 GbE is most efficient when leveraging existing infrastructure where possible, while planning for higher bandwidth, lower latency, and future scalability.

- Cabling and interconnect media become critical at the 10 Gb/s level: choices of fiber (single-mode vs multi-mode), copper (twisted-pair, twin-ax) and proper termination / management are fundamental to achieving full performance.

- Futureproofing is a major theme: beyond 10 GbE there is already momentum toward 40 Gb, 100 Gb and beyond, so designing today’s network with flexibility is advisable.

High-Speed Ethernet Primer & Trends

Ethernet is a group of networking technologies that are designed to facilitate the communication of various devices over a local area network (LAN). Ethernet operates on the Data Link Layer of the open system interconnection (OSI) model, which is the conceptual model used to standardize data packet framing and enabling error-free communication. Where earlier versions of Ethernet used other physical layer interfaces, the main interface for GbE applications is Serial Gigabit Media Independent Interface (SGMII) or the reduced pin variant Reduced Gigabit Media Independent Interface (RGMII). The Media Access Controller (MAC) of an Ethernet network is responsible for the data framing and logical addressing functions where the Physical Layer (PHY) includes the encoding, decoding, and signaling of the physical data transmissions. The PHY interfaces directly with the physical medium, or interconnect, of the network. For high-speed Ethernet, these physical connections are either copper cables or fiber optic cables.

The overall bandwidth capability of an Ethernet connection is a combination of the interface width, or the number of lanes, and the rate per lane in gigabits per second. This configuration allows for some flexibility between individual link speed and the available number of lanes to achieve certain total data rates. There has largely been an acceptance in the networking industry for an 8-lane standard, though more or less lanes may be used in certain applications. This structure dictates the type of copper (CU) and fiber optic cabling that may be used in high-speed Ethernet applications, namely Cu Ethernet Cable, multi-mode fiber optic (MMF) cable, and single-mode fiber cable (SMF).

The designation for a type of Ethernet is the aggregate of the total port bandwidth, and high bandwidth ports can be created from lower rate lanes. For instance, a 50 GbE can be made of two 25 GbE lanes. As of the adoption of IEEE 802.3df™-2024, there is now a standardized x8 structure for 800 GbE, where dual 400 GbE links are already supported for single x8 copper or optical interconnect. This flexibility allows for an 800 Gb/s port to be based on combinations of 400 GbE, 200 GbE, or 100 GbE links configurations, which will likely continue forward as the 1.6 Tb/s Ethernet Task Force continues to develop the standard for the first generation of terabit Ethernet.

This flexibility is crucial as there is a shortening window between standardization and adoption for Ethernet standards in extreme throughput applications. For instance, it is predicted that AI/ML datacenter applications will be adopting the 800 GbE and 1.6 TbE standards just a year or two after official standardization (possibly sooner). This is why for rack-scale connectivity, 400 GbE is the de facto standard, where 800 GbE will soon gain prominence. For automotive applications, of which 100 Mbps and 1 GbE isn’t uncommon, the future will likely see the replacement of legacy networking technology with 10 Mbps Ethernet for low bandwidth applications and up to 10 GbE for high bandwidth applications. In the case of building automation and some industrial automation, 100 Mbps Ethernet is replacing a lot of legacy networking protocols with modern IP stacks. However, there are also trends in building/industrial automation where autonomous robotics and security systems are being deployed that are much more bandwidth heavy than the host of sensors and actuators common to these applications. The more advanced autonomous robotic and security systems are extremely bandwidth heavy, which is why 10 GbE and higher links may be needed to facilitate the data exchange between autonomous intranet and cloud infrastructure or remote operations when remote operation is required. This is a similar circumstance to medical applications that are becoming increasingly remote operated over high speed and low latency Ethernet connections, such as robotically assisted surgery (Robosurgery) and AI/ML assisted diagnoses systems. Smart home early adopters are also moving to 10 GbE from 1 GbE, as smart home security/surveillance and automation systems with higher bandwidths are also becoming more popular. Like with enterprise automation, many of the common sensors and actuators used in smart home automation are relatively low bandwidth, but new security systems with multiple 4k camera streams and either cloud or edge AI/ML algorithms interpreting the data are often over burdening 1 GbE networking systems.

High-Speed Ethernet Interconnect Considerations

Ethernet interfaces and cables are available in a variety of configurations. The main two types are often designated as copper or fiber optic. Though there are also wireless links that can operate as Ethernet interconnects, that is outside of the scope of this paper. Copper-type Ethernet is what most laymen are familiar with, namely the RJ45 connector and 8 strand/4 twisted pair cable. This type of cable, sometimes called patch cable in certain computing applications, is mainly used for shorter interconnect runs (100 m or less) and where cost considerations are primary. Ethernet can also be carried on coaxial or twinaxial coaxial cable, but data rates or maximum interconnect distances in this application are limited as only a single channel is used.

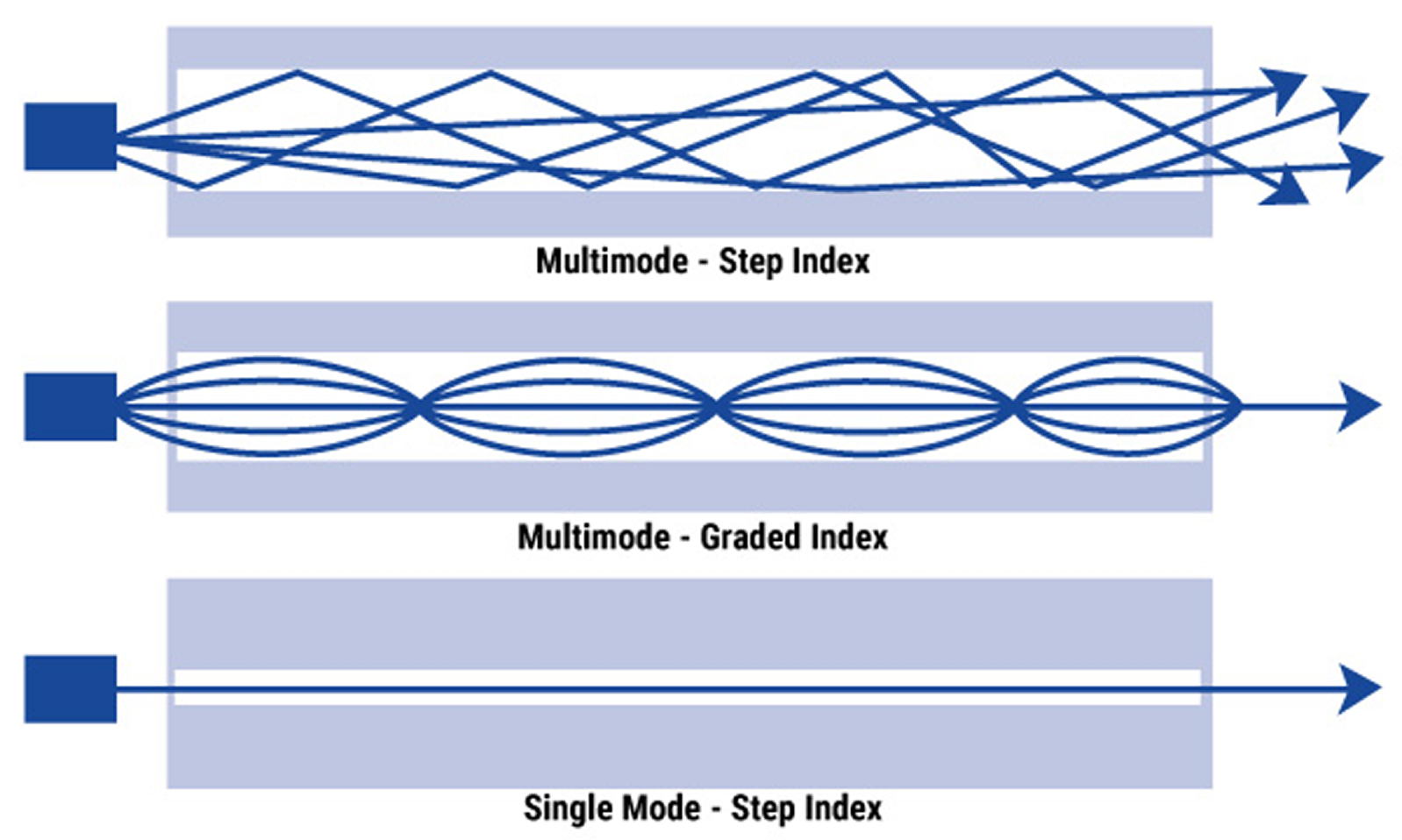

Fiber optic cables can be either single-mode or multi-mode fiber. Multi-mode fiber uses a larger fiber core that can allow for more frequency channels and a wider range of fiber optic transceivers, but at the cost of range. Single-mode fiber can be bandwidth limited compared to multi-mode fiber but is a much more efficient optical waveguide allowing for far greater runs than multimode fiber. Typically, fiber optics are more expensive and complex than copper Ethernet solutions and specialized tools, equipment, and skills are needed to troubleshoot fiber optics.

The following table is an example of the types of Ethernet interconnect commonly available for 10 GbE:

The single mode fiber options have the greatest range of 10 km to 40 km, where the multi-mode fiber is limited to 300 m. The twisted pair ethernet cable is limited to 100 m and twinaxial cable solutions are only rated to 15 m.

As Ethernet speeds have been increased, new categories of twisted-pair Ethernet cable have been created to accommodate these higher bandwidths. The latest category of copper Ethernet cable is Category 8.2 (Cat8.2), which is capable of 40 Gbps (40 GbE) up to 30 m. The various generations of copper Ethernet cable are listed below:

It can be seen from these standardized specifications that copper Ethernet cable isn’t designed for extended interconnect lengths, and future copper Ethernet cables will likely continue this trend of sacrificing maximum distance for greater bandwidth. This has to do with the intrinsically higher losses that twisted pair transmission lines have at higher frequencies. Moreover, even with shielded twisted pair transmission lines there is still some signal leakage and ingress of interference. These factors are significant limiters, along with copper transmission losses, which prevent higher bandwidth usage of these cables at greater lengths.

Fiber optic cable, switches, and fiber transceivers operate using optical lasers or diodes over optical waveguides. The optical fiber is the waveguide that contains the transmitted lightwaves. Matching the fiber optic core to a specific frequency range of light can allow for incredibly efficient transmission, which is why single-mode fiber optics have the greatest range of common networking interconnect technologies.

Image 2: A comparison of multi-mode and single mode light transmission through optical fiber. The single mode step index smoothness is exaggerated as there is still bouncing occurring, just more optically for single mode fiber.

*Source (https://rfindustries.com/fiber-optic-cable-types-multimode-and-single-mode/) requires recreation

As with twisted pair Ethernet, there are also a wide variety of fiber optic options and generations. This is the case for both multi-mode and single mode. For multi-mode fiber the common designations are optical mode (OM) cable generations 1 through 5.

Next Steps

Ethernet is a group of networking technologies that are designed to facilitate the communication of various devices over a local area network (LAN). Ethernet operates on the Data Link Layer of the open system interconnection (OSI) model, which is the conceptual model used to standardize data packet framing and enabling error-free communication.

Optical Mode (OM) Multi-mode fiber optic cable Ethernet range

Single mode fiber (SMF) is either optical single mode one or two (OS1/OS2). OS1 is primarily designed for shorter range indoor environments, such as within a data center, where OS2 is designed for robust outdoor applications for extended runs. To transmit higher data rates with SMF, multi-core cables are used, allowing for several separate lanes.

Though cabling is a critical consideration for fiber optic Ethernet, fiber optics also require transceiver modules. The fiber optic cable connects to the transceiver modules which are then connected to the Ethernet switches and other networking hardware. This differs from twisted pair Ethernet cable, which is often RJ45 connectors that directly plug into the networking equipment. The optical transceiver modules convert the electrical signals to and from the networking equipment to optical/light signals carried by the fiber optic cabling. There are several optical transceiver form factors that are generally compatible from various vendors based on a Multisource Agreement (MSA). These common form factors are Gbic, SFP, SFP+, CFP, CFP2, CFP4, and QSFP28. Moreover, there are range related types of transceivers, either short range at 850 nm (SR), long range at 1310 nm (LR), extended range at 1550 nm (ER), or further extended range at 1550 nm (ZR). Fiber optic cables can have two fiber optic waveguides with two connections to each transceiver, a receiving and transmitting side, or a bi-directional transceiver capable of transmitting and receiving on the same optical waveguide (fiber). Wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) systems, either coarse or dense, are used to carry several wavelengths of light over the same fiber. Hence, when selecting fiber optic equipment, it is essential to match the networking hardware with transceivers and cabling to ensure compatibility and that each element of the interconnect is capable of meeting the link specifications.

Conclusion

The networking equipment and hardware landscape is a mix of several generations of various Ethernet technologies. Where advanced applications in AI/ML, high-performing computing, and massive enterprise networks may make use of the latest Ethernet generations and capabilities, there are many networking applications that are just now seeing 10 GbE, while 1.6 TbE is soon to be on the shelves. 100 GbE is still only common in high performance networking applications with 400 GbE emerging and 800 GbE on the horizon. It is critical for networking professionals to have and understanding of these new Ethernet standards and the diverse range of interconnect hardware that make these technologies possible.

References

- https://standards.ieee.org/beyond-standards/ethernets-next-bar/

Frequently Asked Questions

A: Possibly—but it depends on your cabling. If your current links are Cat 6a (or comparable) or OM3/OM4 fibre and are installed correctly, you may be fine. If your installed cabling is older (Cat 5e, OM1/OM2 fibre) then you’ll likely need upgrades to reach full 10 Gb/s performance and reach.

A: Yes—futureproofing is important. While deploying 10 GbE, consider whether your cabling, pathways, cooling, and equipment racks will support future speeds (40G, 100G). Fibre cabling investments tend to have longer lifespans; in copper, ensure cable trays and pathways have capacity for higher density.

A: Key challenges include insertion loss, return loss, alien crosstalk (especially copper), dispersion and modal bandwidth (for fibre), connector/terminator quality, signal integrity, and power/thermal management of ports.

A: Yes, in the sense that many network designs will maintain mixed-speeds and allow devices at lower speeds to co-exist. But physically you must ensure the link media and hardware support the higher speed segment.

A: Not necessarily. A cost-efficient approach is to identify bottleneck links (e.g., aggregation, backbone) where 10 GbE will make a difference, upgrade those first, while keeping lower-speed links where traffic demands are modest. Then plan phased upgrades as needed.